Third Wave Nicolas Cage

By Eliza Janssen

St Louis Cemetery Number One is only one city block wide, but houses thousands of bodies – some in ornate, private crypts, others stacked unceremoniously in family graves. You’re not allowed to roam the grounds alone, so I had to pay a tour guide a few dollars to lead me through the narrow crypts. He seemed to genuinely care for the dead in a way that’s unique to New Orleans. But I wasn’t here to learn about dead people.

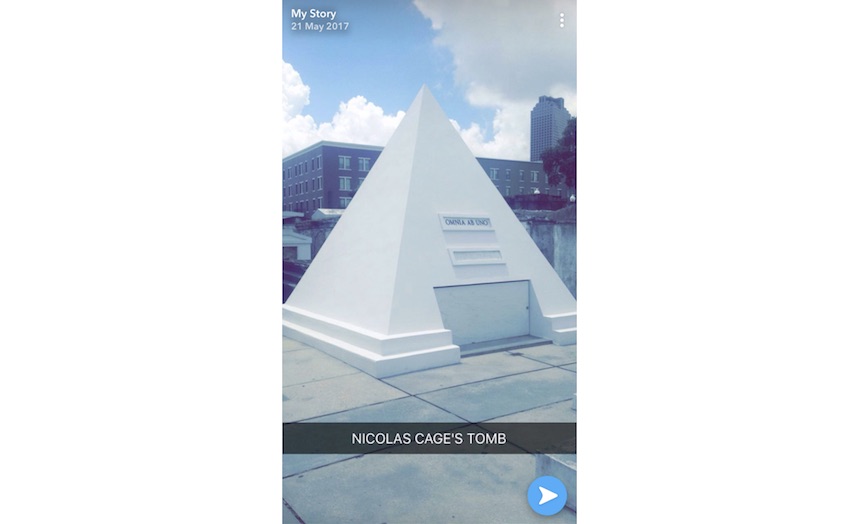

We rounded a corner and faced off with a nine-foot tall white stone pyramid. My tour guide’s demeanour changed – almost embarrassed, he told me that this tomb belonged to Hollywood actor Nicolas Cage. I didn’t have the nerve to admit that this tomb was precisely why I was here.

To be clear, Nicolas Cage isn’t dead. He constructed the tomb in 2009 upon turning 50, and plans to be interred there when he dies. My guide grizzled that the tomb is three times bigger than any other in the cemetery, and is built atop graves from as early as 1780. It’s a monolith – among the skinny stacks of tombs, my eyes physically struggled to adjust to the glare its white surface emits. It reminded me of every time I’ve had my view of a concert blocked by some dickhead’s iPad.

To my mind, there are three prevailing facets to Cage’s public image. The first is of a supremely talented actor – a risk-taker; a dependably stunning collaborator of Coppola, the Coens, Scorsese, Lynch, De Palma, Woo, Herzog; a wildly idiosyncratic performer adored the world over (a quality that can be seen in spades this Friday night when the Astor hosts MIFF’s Cage-A-Thon, 737 minutes of Nicolas Cage movies, back-to-back-to-back).

Cage’s bombastic performance style has earned him enduring acclaim, but it’s also kind of responsible for bringing about his second life – as a living meme. There are currently over four hundred items for sale on Etsy related to Nicolas Cage, all reproductions of his grinning face superimposed over other easy cultural icons for profit. Cage as the Mona Lisa, Cage as Pikachu, Cage as Jesus. For $12.55 I can buy a mug with Nicolas Cage as a lemon, captioned ‘Citrus Cage’, which barely functions as a pun. Making fun of Nicolas Cage is a profitable industry – you can lose a whole afternoon watching lovingly edited YouTube compilations of his loudest, most arm-flailing performances.

The third identity is still somewhat of a cipher – Cage the Human, a fairly secretive figure, boyishly fixated upon superheroes, Elvis, and New Orleanais culture at large. These obsessions surface in film roles like Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009) and Ghost Rider (2007).

It can be argued that the celebrated excess of Cage’s performances is inseparable from the excess of his private life – over the past decade, he’s fallen into trouble with the IRS over approximately $13 million in unpaid taxes. To pay off his debts, Cage has been forced to sell off, among other eccentric collectables; European castles, dinosaur skeletons, and a copy of Action Comics #1, the world’s most valuable comic.

All this misfortune and memetic infamy has only entrenched his status as a cult icon, and has seen him take on an increasing number of film roles. In 2009, the same year Cage’s tomb was constructed, he appeared in four movies; this year he’s in seven. Your typical present-day era Cage vehicle doesn’t do much beyond strapping a thin, action-thriller plot onto Cage’s back and going for broke (Arsenal, 2017), but, every so often, there’s a film like Joe (2013) that tailors its vision to Cage’s unique capabilities as an actor. This year, that film is Mandy (2018).

Director Panos Cosmatos’ sophomore effort after the psychedelic experiment Beyond The Black Rainbow (2010), Mandy is a gnarly, retro hallucination of an action movie. Cage is, at one point, thrown through a glass coffee table covered in cocaine, only to then snort a fat line off a shard of the destroyed table. During this perfectly Cage-ian moment, the cinema cheered, warm with affection for the actor, mocking or otherwise.

But Mandy shouldn’t be dismissed as just an ironic, prog-rock take on John Wick (2014). Cage’s character is a lumberjack living in woodsy, gothic domestic bliss with the titular character (Andrea Riseborough); when a Manson-esque cult kills Mandy, Cage is forced to go quite literally medieval on their asses, alternating between a crossbow and a hand-forged combination of a scythe and a battle axe.

The film’s nightmarish opening act, with all its double exposures and heavy metal imagery, promises a more artistic movie than Cosmatos delivers once the plot turns conventionally bloody, but what follows is still more imaginative than most action movies. There’s gratuitous animated interludes and sword porn, but the film’s most impressive components are Riseborough and Cage. Riseborough has a beguiling crack at making the ‘dead love interest’ role a shade more interesting than normal, as we’re ensconced in her secluded, witchy world for a good while before Cage begins his rampage. And there’s one perfectly staged Nicolas Cage Flip-Out Scene; catatonic with grief, he opens and downs a bottle of vodka while sitting on the toilet, alternately sobbing and screaming with rage. During this scene he’s also wearing no pants.

*

After the cemetery tour, I lay on my stomach on the hotel bed and googled the tomb’s epitaph – ‘omni ab uno’. It means ‘everything from one’. Cage refuses to talk publicly about his religious beliefs; is he referring to himself as the ‘one’, an omnipotent creative force? At the very least, Cage seems to be obsessed with his own mortality, or legacy. Just as in his films, his style and personality can’t be constrained by genre, budget, or good taste – he’s permanently committed, a talent on full display in Mandy.

Mandy

Mandy

My cinema cackled heartily at Cage swinging a chainsaw, wide eyes popping out of a face covered in blood. But he also single-handedly elevates the film’s emotional storytelling, a human, anchoring force amidst all the demonic bikers and burning churches, and Cosmatos’ lustrous, coked-up aesthetic. Mandy synthesises these three versions of Nicolas Cage in a manner few other films achieve.

Jóhann Jóhannssón’s lurching score is the only thing we hear as Cage witnesses Mandy’s brutal murder, restrained by barbed wire and unable to rescue her. We just see his face, frozen by trauma – an unchanging expression of utter misery plastered across the screen for an extended moment. His reaction is more upsetting than the violence itself, full of the magnetic, hysterical excess that defines a Cage performance. I had felt that same sense of excess when I stood in front of his empty grave; Nicolas Cage doesn’t do subtle, in life or in death.